Contracting options for offsetsintermediate

Buyers can contract for carbon offsets in a number of ways –¬ the most suitable option depends on the purchaser’s desired engagement with the project, offset demand, level of experience in offset trading and views on additionality. Broadly speaking, earlier sales mean better terms for buyers, and gives them more control over project quality. But they also increase the level of risk and the time it takes until they receive the offsets.

Key message

More experienced buyers may prefer to work directly with a project developer through an over-the-counter transaction, while newer buyers will let a broker or aggregator handle it for them, which could simplify the process but be more expensive and weaken the additionality argument. As the voluntary carbon offset market grows and involved parties work to improve its legitimacy, companies can also expedite their offset purchases through an exchange.

#When

Offsets may be sold at any point during the project lifecycle: some developers look to agree at sales early on through forward contracts to lock in the price and other terms. For example, a prospective buyer could support the development of a new methodology or protocol, or invest directly in a project. While this should give them more knowledge of and control over project quality, it is also more resource- and time-consuming.

Other buyers wait until the offsets are generated, certified and issued before undertaking spot market sales. Regardless of when the sale occurs, developers are generally only paid once the offsets have been delivered, although advance payments are possible.

The price of an offset will depend on the contract terms. For example, offsets are generally more expensive if the emission reductions are guaranteed, meaning they have either already occurred or will in the near future. In such a case, the seller may be liable for contract default if they fail to deliver the agreed units. Prices will typically be lower for intended emission reductions to account for this risk.

#Over-the-counter

Though more complicated, buyers can invest directly in a project, claiming a portion of the offsets as they are produced and potentially saving on transaction fees. For purchasers that place extra emphasis on additionality and marketing emission reductions to their stakeholders, direct investment can lead to deeper engagement with a project. Alternatively, companies can lock into a multi-year contract for a set amount of offsets through an emission reduction purchase agreement, or ERPA, similar to a power purchase agreement (PPA) in energy markets. The long-term revenue certainty of an ERPA generally gets buyers access to cheaper offsets from a project because it helps that project developer secure financing.

#Intermediaries

Some companies work with a third party – known as a broker – to help them choose and contract offsets. In most cases, they will bring a list of projects to a customer, purchasing offsets and retiring them on the customer’s behalf. They also occasionally pre-purchase offsets directly from developers and then sell them to customers at a later date for a premium. Buyers can specify criteria like the amount of offsets they want to purchase, as well as the sectors and regions they want to buy from. This greatly reduces the complexity of purchasing offsets for a buyer relative to other options, though it can extend the timeline for buying them, compared with going through an exchange. Most brokers’ business models include an extra per-unit charge on each offset purchased, meaning contracting for offsets through a broker is the most expensive route – even more so than going directly to a developer.

Another option is to purchase from an aggregator. Unlike a broker, these intermediaries purchase and take ownership of offsets from small suppliers to sell them at a more competitive rate to brokers or buyers. This approach is suitable for buyers looking to purchase only a small volume of offsets, although they may only have access to basic information on the projects. Aggregators have accounts on registries and can retire the offsets directly on behalf of buyers. They are most common in sectors like agriculture where the projects that produce offsets are smaller and don’t have the balance sheets to begin generating credits on their own.

#Exchange

The fastest and perhaps least involved process involves contracting offsets through a commodity exchange. Developers and brokers can list their offsets on an exchange for anyone to buy, though once listed these offsets cannot be sold elsewhere. While exchanges do give developers additional exposure, they typically charge a commission fee on each sale, which can drive up prices.

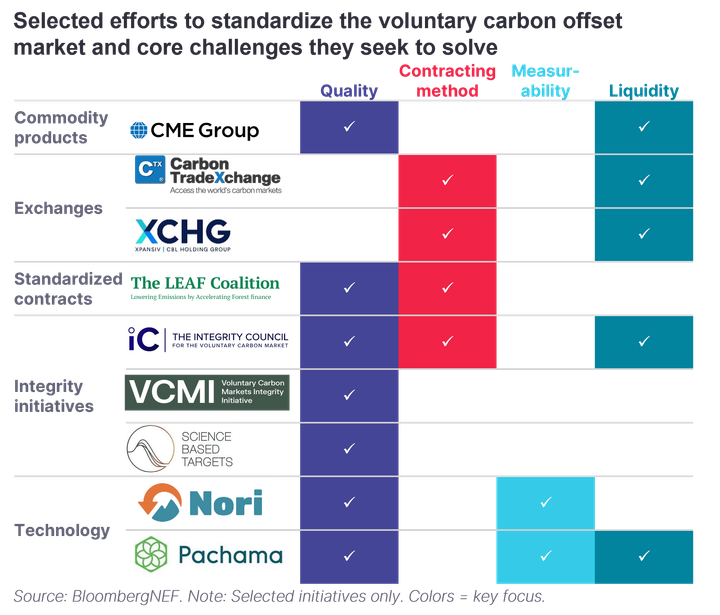

Furthermore, while companies using an exchange get information on the origin of any offsets they purchase, there is no direct engagement with developers, weakening a buyer’s additionality claim. In many ways, it is hard to even classify carbon offsets – especially those of high quality – as a commodity. Developments like exchanges are the first step in standardizing offset buying and turning it into a more liquid and dynamic market.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when the web platform goes live.