Mechanisms to control carbon marketsintermediate

The vast majority of compliance carbon markets incorporate mechanisms to help control the market to avoid shocks. These are a risk because it is challenging to forecast emission trajectories accurately and a fixed volume-based cap cannot automatically respond to changes in the supply-demand balance. Governments may also implement control mechanisms to avoid excessively high or volatile prices, as too much variability can undermine confidence in the program.

Key message

Almost all emissions trading programs have provisions or levers that can help control the market. The most common types are price restrictions on permit auctions and reserves. The majority are also triggered by pre-defined rules, often linked to price, which help to have a longer-lasting impact on the market and increase certainty for investors and scheme participants.

#Why they are needed

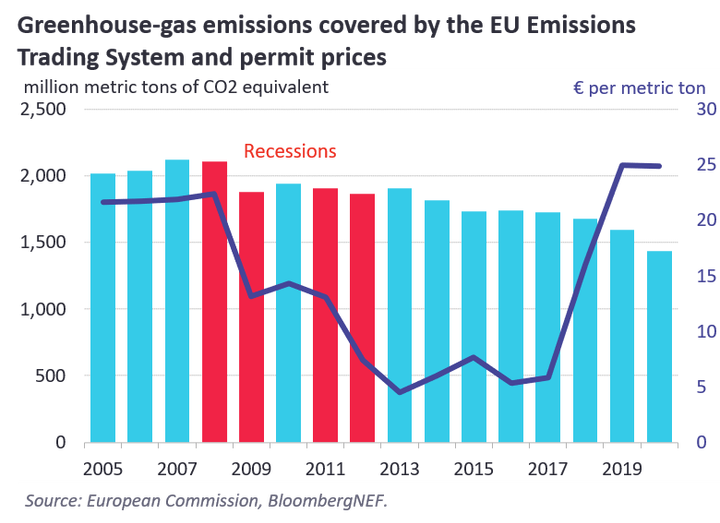

The reason why market-stability measures have become more common can be seen with the example of the EU when it faced a double-dip recession over 2008-13. As a result, emissions covered by the bloc’s cap-and-trade program declined by 11% from 2008-09 and carbon prices by 41%. They fell again across 2011-12 by 2% and 43%, respectively. Because the emission cap was not adjusted and permits could be banked into future years, a substantial oversupply accrued, keeping prices down. Note that banking in itself is not a problem: in fact it can help smooth price fluctuations over time.

Market-stability mechanisms vary in a range of ways: the most common type is restrictions on carbon prices in permit auctions. For example, the US-based Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative applies a floor (lower limit) on prices, while California’s program has a floor and ceiling (upper limit). The second most common mechanism is the use of reserves, whereby a pot of carbon permits are set aside and can be injected into the market if certain conditions are met. For example, the UK has a Supply Adjustment Mechanism, and several Chinese pilot emission trading schemes also have reserves. Alternatively, the government, exchange or another player may intervene in the market.

#Triggers

Most stability mechanisms are triggered by market prices based on pre-defined rules. For example, the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme has a Cost Containment Reserve whereby if an auction clearing price in is at or above a specified trigger price, then a certain share of allowances is released for auction. In Beijing’s pilot scheme, the exchange can intervene in trading if prices go above or below 20% of the reference price, which is the weighted average price of all transactions on the previous trading day.

The EU’s Market Stability Reserve (MSR) is a one of the few measures that depend on the supply-demand balance. If there is a significant market surplus (based on the total number of allowances in circulation), the European Commission reduces the volume of allowances to be sold by auction. In the event of a deficit, additional permits could be auctioned.

A few mechanisms are initiated by both price and volumes. In the Chinese province of Hubei, for example, the government can intervene in the event of price fluctuations, supply-demand imbalances or market liquidity issues.

The EU’s MSR follows a set of pre-defined rules to determine when it is triggered, in order to increase market certainty. By contrast, for other mechanisms, the decision may be at the discretion of the government or other authority, as is the case for some pilots programs in China. Uncertainty over whether the authority will take action and in what way has meant that previous interventions in South Korea’s carbon market have only had a temporary effect, as shown in the chart below. In China, regional governments decide when to use a stability mechanism based on rules that may not always be written down. This lack of transparency has helped increase price volatility.

Some programs are a mix. The UK’s Cost Containment Mechanism is triggered under certain circumstances, but permits are only then auctioned if the price increase does not correspond to market fundamentals – and this is decided by the government.

#Responses

Once a market-stability mechanism is triggered, the response can take various forms. The most common actions are to limit prices – for example, floors or ceilings in permit auctions, or in the secondary market. Alternatively, with a reserve, allowances may be withdrawn or injected into the market. For example, in Shenzhen in China, 2% of the total cap is kept as a government reserve for market stabilization and in the case of fluctuations, the Ecology and Environment Bureau can sell extra permits from the reserve at a fixed price. The Shenzhen government can also purchase back up to a tenth of the total cap.

Other types of government or exchange intervention are possible. In South Korea’s emissions trading program, the government-appointed Allocation Committee may implement a range of measures in certain circumstances, such as if the permit price of six consecutive months is at least three times higher than the average price of the preceding two years. It has a raft of responses available, including additional auctions of reserve allowances, limits on the number of permits allowed in an entity’s account, changes to borrowing or offset limits, and a temporary price floor or ceiling.

As with the trigger, the decision on the response may be based on a set of pre-agreed rules, as tends to be the case for price controls and some reserves – for example, the EU’s MSR. For the other types of mechanisms, the response is more likely to be decided by an authority – for example, if prices vary by more than 10% or 30% in a day, the Chongqing Carbon Emissions Exchange in China can implement stability mechanisms, such as temporarily suspending trading or introducing a holding limit.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when the web platform goes live.