Goals and impact of carbon pricing

basic

|

25 Sep 2024

Goals and impact of carbon pricing

Carbon-pricing policies aim to make polluters pay for their greenhouse-gas emissions. Without such programs, companies and individuals face no direct costs from this pollution nor any of the consequent costs borne by society such as the effects of climate change and impact on health. Existing schemes have helped to spur and accelerate emissions reduction, promote the use of cleaner technologies, and bring other economic and social benefits.

Key message

The objective of a carbon price is to ensure that the producers of greenhouse-gas emissions pay for the costs of such pollution. Such schemes have proved effective at reducing emissions, with social, economic, and physical benefits. But devising an effective carbon-pricing policy is tricky and even an effective CO2 tax or market alone will not enable a government to meet its net-zero target.

Effects

Companies and individuals bear no direct costs from their emissions of greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere. They, therefore, do not base their production, consumption or investment decisions on these negative externalities, potentially leading them to emit more than they would otherwise do so. But such pollution does bring costs, which have to be borne by society in general. Climate change due to man-made greenhouse-gas emissions is already causing “dangerous and widespread disruption in nature and affecting the lives of billions of people around the world”, according to the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The ultimate goal of a carbon price is to drive polluters to reduce their greenhouse-gas emissions, for example, by decreasing demand for energy or materials, and switching to cleaner fuels. It is, therefore, meant to be more effective than a traditional regulation on emissions. For example, if a government introduces a performance standard limiting emissions per unit of output, companies are only spurred to constrain greenhouse-gas output to the standard set. In contrast, carbon pricing incentivizes emission reduction and charges a price for each additional ton not reduced.

A cap-and-trade program is meant to motivate companies to cut their emissions if the cost of that reduction (or abatement) is lower than the carbon price. If it is higher, a company would be incentivized to buy a permit. In this way, carbon pricing is meant to be more effective at spurring emissions reduction than simple regulation.

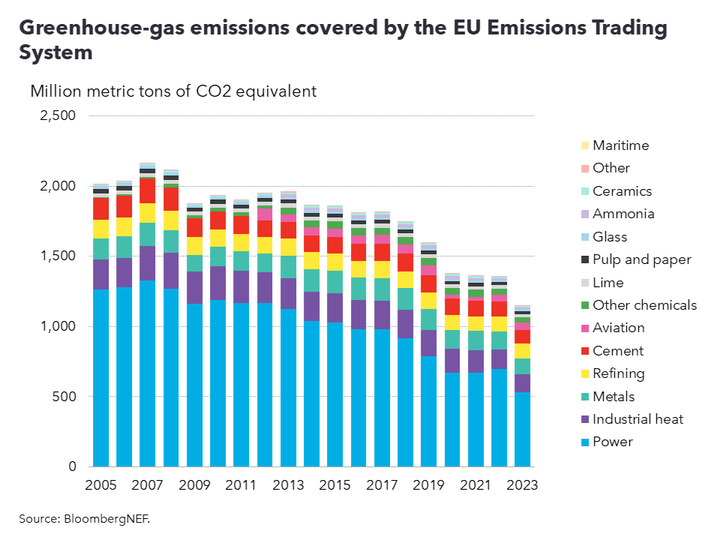

Indeed, there is evidence that carbon pricing can be effective. For example, companies participating in the EU Emissions Trading System reduced emissions by 43% between 2005 and 2023. The biggest decrease came from the power sector, principally due to electricity generators switching from coal to the less carbon-intensive natural gas. Fuel switching is an example of operational abatement, while permanent abatement, such as building renewable power plants, has been relatively modest to date.

The carbon price in California – home to the biggest carbon market in the US – has been high enough to phase out coal and gas for power generation. The state, therefore, cut electricity-sector emissions by 31% between 2013 and 2022.

Some jurisdictions have begun to see evidence of a CO2 price driving permanent abatement. For example, Sweden’s carbon tax, which now has one of the highest prices in the world, has played a significant role in the 90% reduction in emissions from heating of homes and premises from 1992 to 2022, based on data provided by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. This decrease was principally driven by households and district-heating systems permanently switching away from oil and other fossil fuels to electric technologies and bioenergy.

Carbon pricing can also have benefits for human health: the carbon market in the Northeast US – the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) – has lowered particulates from power plants, helping to avoid asthma attacks, pre-term births and cases of low birth weight and autism spectrum disorder in children, according to a 2020 study. These health benefits had an estimated economic value of up to $350 million.

The RGGI has also generated economic benefits, creating over 44,000 years’ worth of work in its first decade, according to a 2018 report. For example, the scheme spurred companies to seek energy-efficiency savings, creating demand for workers to undertake energy audits, and provided training.

Challenges

Nevertheless, designing a carbon tax or market is a complex task. The scheme needs to be bold enough to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. But it also needs to be politically acceptable and not hurt local industry’s competitiveness. Carbon trading also brings costs and challenges, as well as opportunities, for companies. For example, a 2015 research report estimates that a utility company in the EU ETS faces monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV)-related transaction costs of $0.02-0.23 per ton of annual emissions, depending on the size of the company.

Carbon pricing is also not a silver bullet. Complementary policies will be needed for countries wanting to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century. For example, a CO2 tax or market may not be sufficient support to spur innovation and technological change, meaning other measures like financial incentives may be needed. Additional programs could be required to drive the deployment of clean infrastructure (such as electric-vehicle chargers) and to ensure that the benefits of the climate transition are shared widely, while supporting companies, workers and local communities that could be affected.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when there are new Carbon Knowledge Hub releases.